Play the song!

Texas Legacy Fest- In a NutshellThe Festival- Coming April 12-13, 2013

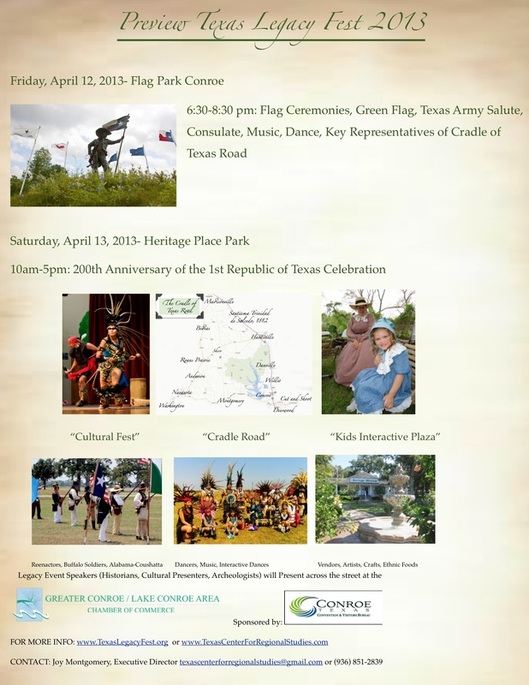

On Saturday, April 13th, and the preceding evening, Conroe, Texas will be the scene of a festival unique in Texas History. On these dates, celebrated will be the 200th anniversary of the birth of the First Republic of Texas, 1813—the Green Flag Republic. A varied assortment of key people locally and from around the state will be involved, including Aztec dancers, speakers, authors, educators, students, government personal, state and local, musicians, artists, and much much more. The focus will be on defining and appreciating our multicultural legacy from this historic event which played a pivotal role in weaving together Mexican, Texas, French and United States history. But this is not all. The event will be celebrated in conjunction with places in close proximity which, taken as a unit, comprise what may be appropriately called a “Cradle of Texas Road. |

Texas Legacy Fest- Expanded ViewThe Texas Legacy Festival will be held April 12th and 13th; it will be celebrating the 200th Anniversary of the 1st Republic of Texas, 1813 also known as the Magee-Gutierrez Expedition. We are celebrating the beginning dream of Texas, the idea that this first republic fought for by a combination of various cultures (african, hispanic, native american, and European decent). They won the first Republic but lost it when the cultures fought divided in the Battle of Medina (the bloodiest battle in Texas history).

At this celebration we will thus have representations in dance, music, and food from each culture including: Light Crust Doughboys, Aztec Dancers, Mayan Dancers, African American Buffalo Soldiers, the Texas Army, and Ballet Folklorico. We have several local museums contributing a kids corner for hands on pioneer activities and games. In all of this celebration there is an additional component of the Cradle of Texas Road. The Festival will have an area devoted to the cities represented. There, each city will have a booth and have a time to present a piece on their city and its history. In addition to this on Friday, April 12th at the Flag park in Conroe 13 Cradle of Texas road representatives will raise 13 flags of Texas History. This is a unique concept about which we are all most excited about and we hope to make the Texas Legacy Fest and the Cradle of Texas Road an annual event. The book of the history and present "movers and shakers" of the Cradle of Texas Road will be going to press. In addition there is a mural that will be created dedicated to the Cradle of Texas Road, an app, a 7th grade history version for the local schools and an interactive school ebook. For more information please visit our websites: www.TexasCenterforRegionalStudies.com www.TexasLegacyFest.org and soon a website devoted solely to the Cradle of Texas Road and another to the book We hope to have the local children become interested in their history and the beauty of local cultures...to foster a since of togetherness for future generations. Last year the Texas Legacy Fest in Navasota hosted Dr. Terry Colley and the Cultural Attache of France for the Rededication of the statue of La Salle given by France to Navasota. |

Our (Amazing!) Key Contributors:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Celebrating Togetherness

Celebrating Togetherness:

Mexicans, Anglos & the First Republic of Texas, 1813

by Robin Navarro Montgomery, PhD

Preface:

Entering the second decade of the twenty-first century, the United States is being polarized alarmingly along racial and cultural lines. Of immediate concern is the widening breach between Hispanics and those of Anglo-American heritage. University of New Mexico professor, Charles Truxillo, for instance, is projecting that before the end of the 21st century a new country, to be called “The Republic of the North”, will be carved out of the southwestern states of the US and the northern states of Mexico.

This study addresses the crisis of social fragmentation in our country by laying an historical foundation upon which to resurrect a sense of common

national identity. Explored here are the shared roots of Anglo-American and Hispanic-American cultures in events surrounding the rise of the First Republic of Texas. Emphasized is the direct link between these events and the drive for Mexican independence from Spain which Father Miguel Hidalgo initiated on September 16th, 1810.

By portraying the decisive role of the blending of Anglo and Hispanic cultures in the rise of the first republic, the book is “Celebrating Togetherness.”

Acknowledgements:

Providing Inspiration for this study was the Visionaries in Preservation, VIP, Program of the City of Navasota,TX under the direction of City Manager, Brad Stafford, in cooperation with Mayor, Bert Miller, and former City Councilman, Russell Cushman, and the Montgomery County Genealogical and Historical Society, MCG&HS.

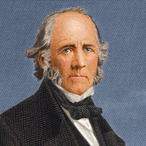

About the Author:

Robin Montgomery holds a PhD from the University of Oklahoma and has been a professor at Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Troy State Graduate Program in Europe and Oxford Graduate School. He is a member of the Oxford Society of scholars and has published extensively in international relations and in Texas History. His books on Texas History include, The History of Montgomery County(1974,86), Cut’n Shoot, TX: The Roy Harris Story(1984), Tortured Destiny: Lament of a Shaman Princess(novel-2001), Historic Montgomery County(2003), Indians & Pioneers of Original Montgomery County(2006 & 2010), March to Destiny: Cultural Legacy of Stephen F. Austin’s Original Colony(2009), co-authored with Joy Montgomery Images of America: Navasota (2012), and in publication: Roy Harris, Cut and Shoot, TX

Published by Texas Herald Press, 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Preface

Introduction

Chapter I:

Mexico(New Spain): From Cortéz to Hidalgo

Chapter 2:

The Era of Mexican and Texas Patriots Together

Selected Bibliography

Introduction:

In 1813, Texas was a part of Mexico which was, in turn, a colony of Spain. On April 6th of that year, the first independent Republic of Texas was established. Earlier, seeking to arouse his Mexican countrymen to the cause of independence, the soon to be president of the republic expressed the multicultural mix of his followers:

“Rise en masse, soldiers and citizens: unite in the holy cause of our country! I am now marching to your succor with a respectable force of American volunteers who left their homes and families to take up our cause, to fight for our liberty. They are the free descendents of the men who fought for the independence of the United States: and as brothers and inhabitants of the same continent they have drawn their swords with a hearty good will in the defense of the cause of humanity: and in order to drive the tyrannous Europeans beyond the Atlantic.” (bib.: “The First Republic of Texas”)

The man expressing these words was Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, whose mentor and inspiration was Miguel Hidalgo, a lowly parish priest in Dolores Mexico. In that town, on September 16, 1810, Hidalgo had given vent to words known to all lovers of freedom as the “Grito de Dolores”, a cry for freedom under the banner of the Patroness of the Americas, “Our Lady of Guadalupe”. “Long live Religion, long live America,” he cried. Hidalgo’s message spread across the length and breadth of his country, giving birth to a movement which by 1821 resulted, finally, in freedom for Mexico from its Spanish overlords. In the early stages of that struggle, Hidalgo commissioned Bernardo Gutiérrez as a Lt. Colonel in his Army.

Exploring the link between Hidalgo, Gutiérrez, and volunteers from the United States in establishing the first Texas Republic is the primary thrust of our story. We will begin with an initial survey of the historical class structure of Mexico, then proceed to the events giving rise to the “Grito de Dolores”. We will follow with a survey of the repercussions of Hidalgo’s Grito including the rise of Gutiérrez and the establishment of the first Republic of Texas.

The conclusion will explore the significance of these events for the blending of Hispanic and Anglo-American cultures.

Chapter I

Mexico (New Spain):From Cortéz to Hidalgo

Founding of New Spain & its Culture:

In 1519, an adventurer based in Spanish-controlled Cuba, Hernán Cortéz, undertook the leadership of an expedition to the coast of the mainland to the west. Upon landing, he established a town which he called Vera Cruz, the True Cross. Named for its colonial master, Spain, the surrounding land was known as New Spain. By 1522, Cortéz and his army had conquered the dominant civilization of the vast area of New Spain, the Aztec Empire.

Over the next three centuries, a highly stratified society emerged in the ever-expanding Spanish Colony. At the apex of society were those who enjoyed the accident of having been born on the peninsular of Spain. They were known as peninsulares, and they held the key political positions of the land, starting with the position of viceroy, vice king, the direct representative of the king of Spain. Next in the social hierarchy were those of essentially pure Spanish descent but born in New Spain. There were called criollos (creoles). Finally came the mixed bloods, those of some Spanish descent. First among these were the mestizos, of Spanish and Indian blood, then there were the mulattoes, a mixture of Spanish and African-American lineage. Holding the bottom rung of society were the Indians and African-Americans.

Over time the position of the Indian in New Spain became progressively more untenable. Not only were their numbers decimated by diseases brought by the Europeans, for which the Indians had no immunity, but the Indians also fell liable for tribute in time and labor to their Spanish masters.

Sustenance to cope with this condition of servitude came for the Indian in a dramatic fashion one day in January 1531. An Indian peasant, Juan Diego, now St. Juan Diego, was worshipping at the shrine of the Indian serpent goddess. To his grand surprise, amid bright light and bird song, the Virgin Mary appeared to him. She requested that Juan tell the Spanish authorities of her, asking them build a shrine to her on the sacred hill on which she stood. The faithful Indian did his best to meet the grand lady’s request, but alas, was unable to meet success.

Undaunted, the lady appeared to him a second time in the same place. This time she asked him to climb to the top of the hill and there pick red roses, placing them in his cloak. Although it was the dead of winter and besides, only cactus had ever grown on this hill top, the faithful Indian obeyed. And the roses were there. Placing them in his cloak as requested, he presented them to the priest. To the surprise of all, appearing on the cloak were not roses by an image of the lady made without human hands.

Placed in the nearby town of Guadalupe, the cloak became a shrine know as the “Virgin of Guadalupe.” Copies of the shrine appeared throughout the Americas. Worship of the Patroness of the Americas had begun.

Change Agents:

The beginning of the end of the highly stratified society of New Spain came in 1808. In that year, the French Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, placed his brother, Joseph, on the throne of Spain. Napoleon took the legitimate heir apparent to the Spanish crown, Ferdinand VII, into captivity in France.

The reaction in New Spain to Napoleon’s coup was along class lines. The peninsulares supported the viceroyalty, hoping that way to continue to exercise power. On the other hand, the criollos and higher level mestizos, for the most part, looked to find some way to gain independence for New Spain in the name of the deposed king Ferdinand. The lower level mestizos and mulattoes, Indians and African-Americans, generally remained out of play of the politics, living as they had for centuries.

Rise of Miguel Hidalgo:

Miguel Hidalgo was born on May 8, 1753, near Guanajuato, New Spain. The early years of his education were

at Valladolid, now called Morelia, and he became a priest in 1779. Along the way, he learned several Indian dialects as well as French. The latter language he used as the bridge to take him to knowledge of the philosophy behind the French Revolution of 1789. Reading this literature was considered sacrilege in New Spain in those times.

By 1810, Hidalgo had become a priest in the village of Dolores, New Spain, not far from his native Guanajuato. He would on occasion travel to the nearby town of Queretaro where he would visit with other criollos and more cultured mestizos of like-minded philosophical bent. It was on these occasions that he became involved with a group bent on revolting against the French-supported peninsulare establishment.

With a loose coalition including most prominently a criollo military officer named Ignacio Allende, Hidalgo marked December 1810 as the time for the revolt to begin. Alas, however, word of the plan leaked to the peninsulare authorities prompting a momentous decision from Hidalgo, would he run or would he fight?

Hidalgo chose the latter option. It was thus on September 16, 1810, that Miguel Hidalgo rang the bell summoning his lower class flock and announced that the time had come for revolution in the name of religion and Independence, as subjects of King Ferdinand VII of Spain. Animated, his

flock followed him, bent on taking Mexico City. Along the way, they took on a banner emblazoned with the Image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. In the name of the holy catholic religion, they would rout the Spanish royalists, now under the influence of the French apostles of the secular ideas of the French Revolution and Enlightenment.

As Hidalgo and Allende led their undisciplined army toward Mexico City, violence and massacres were rife everywhere in their path. So much so that on the outskirts of the city, with victory in his grasp, Hidalgo hesitated, to the chagrin of the more military-minded Allende, and decided to forfeit a sure victory. Instead, he turned his army around and headed for Texas, seeking to gain support in the United States.

By early 1811, Hidalgo’s Army had lost several key battles but had managed to get to the state of Coahuila just below the line of the present border of Texas. During this time, Coahuila and nearby Nueva Leon as well Nueva Santander north of the Rio Grande were sympathetic to the insurgent cause. So was Texas.

Meanwhile, in San Antonio:

In 1773, San Antonio had become the capital of the Province of Texas. As Hidalgo was making his way north, the Spanish Governor in charge of the state was Manuel Salcedo. On January 21, 1811, Juan Bautista de Las Casas initiated a coup de etat against Salcedo. Salcedo received a sentence from the new administration to house arrest in a hacienda or plantation outside of Monclova, Coahuila. Managing the hacienda was an ally of Hidalgo named Ignacio Elizondo.

The sojourn of Salcedo at the hacienda of Elizondo was destined to be short-lived, for on March 2, 1811, the regime of Las Casas suffered defeat. His place was taken by Juan Manuel Zambrano, a loyalist of the royalist cause. The new regime reversed the sentence of Manuel Salcedo, and then sent troops to the Elizondo hacienda to release the former governor. Their task was easy, for Elizondo, the overseer of Salcedo, had by the time of their arrival, deserted the insurgent cause.

The fate of Miguel Hidalgo, Spring and Summer 1811:

These events coincided with the arrival of the main forces of Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende into northern New Spain. Hearing that Hidalgo was in the area, the traitor to Hidalgo’s cause, Elizondo, mustered a force together, and under the authority of a revitalized Manuel Salcedo, succeeded in luring Hidalgo and his army into a trap. The patriotic captives were escorted to Chihuahua where Salcedo presided over their trial, sentencing Hidalgo, Allende and the main leaders to death. Not only were they killed, but Hidalgo and Allende, along with two other members of Hidalgo’s high command, had their heads severed from their bodies and placed on pillars in public at Guanajuato. There they remained for some ten years.

Chapter II

The Era of Mexican and Texas Patriots Together:

Enter Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara:

Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara was a blacksmith of criollo lineage who spread revolutionary flyers within areas in the vicinity of the eastern reaches of the Rio Grande. As Hidalgo made his way north, Bernardo greeted him, receiving in return a commission as a Lt. Col. Hidalgo also made Bernardo his envoy to the United States. Although it was just after Hidalgo suffered death, Bernardo Gutiérrez did indeed make his way to the United States where he visited with Secretary of State James Monroe. A representative of Monroe, William Shaler, subsequently joined Gutiérrez in Louisiana and accompanied him to Texas, entering the state in August, 1812.

With Bernardo Gutiérrez as co-leader of forces was an officer of the United States Army, Augustus Magee, who soon resigned his United State’s commission. The resultant Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition was able easily to capture Nacogdoches, then it was on to the Trinity where they overcame the Spanish forces of Trinidad. From here they headed for San Antonio. En route, as they approached the Colorado River, word came that Manuel Salcedo, now back in power as governor of Texas, was awaiting them. Hence the expedition turned south toward Goliad and captured the Bahia Presidio there.

Governor Manuel Salcedo’s Army soon laid siege to the fortress of Bahia. However, with time, the revolutionaries ventured out victorious and set their sights on San Antonio. It was as they neared that city that Bernardo Gutiérrez spread the word to the citizens of San Antonio, quoted in the introduction, that he was on the way with support from Anglo-Americans.

The Green Flag Republic:

By early April, the expedition had achieved success. On April 6, 1813, Gutiérrez proclaimed the Republic of Texas and proceeded to write a constitution. Before reaching San Antonio, Gutiérrez’s military cohort, Augustus Magee, had died during the Bahia siege. However, the green flag that Magee had fashioned at the beginning of the Gutiérrez-Magee expedition in honor of his Irish ancestry symbolized the new republic, indeed known as the “Green Flag Republic.” Thus, the first Republic of Texas was headed by a Mexican, heir of Miguel Hidalgo’s revolution, and under a symbol of Irish-American lineage.

As President of Texas, one of the first acts of Gutiérrez was to bring to justice Manuel Salcedo and his cohorts, sentencing them to be imprisoned outside of the capital city. Thus did Bernardo Gutiérrez avenge the death of the executioner of Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende and their key followers.

Unfortunately, this great deed was mishandled as Antonio Delgado, the man in charge of the forces escorting Manuel Salcedo and company, had revenge on his mind. Salcedo had been responsible for the execution of Delgado’s father. Consequently, just outside of San Antonio, Delgado called for Salcedo and his colleagues to dismount and proceeded, with the help of his followers, to slit their throats. Not only this, but the executioners returned to San Antonio to brag about the matter.

This gruesome incident led to the alienation of many of the Anglo-Americans who were affiliated with the Gutiérrez government and they consequently left the city and state. Whether Gutiérrez had sanctioned the massacre of the Salcedo group is yet debated among historians. What seems for sure, however, is that this was one of the reasons that he was forced from office on August 4, 1813.

The Battle of Medina:

The man replacing Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara as President of the Republic of Texas was José Alvarez de Toledo. After an initial skirmish with a force under Ignacio Elizondo, on August 18, 1813, Toledo led some 1400 hundred troops into battle against the royalist General Joaquin Arredondo. This was near the Medina River. In the bloodiest battle in Texas history, all but about 100 of Toledo’s followers suffered death.

A primary cause of the debacle lay in Toledo’s decision to divide his forces by race. He created separate groups of insurgent Mexicans, Indians and Anglo-Americans. There was at least one African American among Toledo’s troops, a man named Thomas. The racial division of forces proved highly inefficient as representatives of these groups had been used to working together. Apart, they were ineffective. United upon their entry into San Antonio they had successfully proclaimed the first Republic of Texas. Later, however, divided, the republic fell, defeated. This defeat, however, failed to sever the link between Gutiérrez and Texas.

Gutierrez supports later filibustering expeditions into Texas:

In 1817, Francisco Mina, a Spaniard, sought to continue the Hidalgo rebellion by engaging royalist forces in southern Texas. Lending liaison aid and support to the unsuccessful Mina Expedition was Gutiérrez.

The First Lone Star Republic:

During 1819 to 1821, Dr. James Long embraced filibustering expeditions to Texas. The first expedition set up bases along both the Trinity and Brazos Rivers while the last operated at Bolivar Point off Galveston Bay. Representing the government of Dr. Long was a flag emblazoned with a white lone star against an immediate red background coupled to red and white stripes. Alternately, for a time, was a solid red flag with a white star.

Playing an endemic role with Long was the peripatetic Bernardo Gutiérrez. Gutiérrez was a member of Long’s council of advisors and slated to be vice president, should the revolution have succeeded in implementing the second Republic of Texas.

Interestingly, the person whom Long projected to fill the role of president was José Felix Trespalacios of the Mexican state of Chihuahua, a revolutionary also drawn from circles heir to Hidalgo. By the time of the Long Expedition, Trespalacios had been imprisoned several times by royalist forces; the last time he was placed among survivors of the ill-fated Mina Expedition. Managing to escape, Trespalacios made his way to New Orleans. There he made contact with James Long, becoming the nominal commander of the Long Expedition. He survived to become the first president of the post Spanish era Mexican State of Coahuila y Texas.

Gutiérrez de Lara recognized in an independent Mexico:

The final liberator of Mexico from Spanish rule was Augustin de Iturbide, who formally recognized the efforts of Gutiérrez de Lara for his significant accomplishments toward Mexican Independence. Reflective of the gratefulness of his country, Gutiérrez received election to the governorship of the Mexican State of Tamaulipas in

1824 as well as being named commandant general of that state in the following year.

In Conclusion:

It has been shown that by extension, Hidalgo’s revolution was intrinsically intertwined with events in Texas and the United States. Linked to Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, the phase of the revolution in Texas reflected an intercultural mix, militarily, socially, politically and in terms of religion, a glorious chapter in the history of both Mexico and the United States.

Truly, on September 16th , and on April 6th, in unity we can proclaim, “Viva Hidalgo, Viva Mexico, Viva Texas and Viva los Estados Unidos”!

Selected Bibliography:

BOOKS:

Carter, Hodding. Doomed Road of Empire. New York: McGraw Hill, 1963.

Foote, Henry Stuart, Texas and The Texans. Vol. I; Austin: The Steck co., 1935.

Garrett, Julia K., Green Flag Over Texas: NY-Dallas: Cordova Press, 1939

Montgomery, Robin. The History of Montgomery County, TX. Austin: Jenkins co., 1974, & sesquicentennial ed.,

Conroe Sesquicentennial Committee, 1986.

Parkes, Henry Bamford. A HISTORY OF MEXICO. 3rd edition; Boston: Houghton Mifflin co., 1960.

Putnam, Robert. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York

Simon & Shuster, 2000.

Yoakum, H., History of Texas. Austin: Steck co., 1855.

ARTICLES:

Gutierrez de Lara, “ 1815, Aug.1 J.B. Gutierrez de Lara to the Mexican Congress. Account of Progress of

Revolution from the Beginning.” pp 4-29 in Lamar Papers, vol. I,(Austin-NY: Pemberton Press, 1968.)

“The First Republic of Texas”. New Spain-Index. Sons of Dewitt Colony.

http://us.mg4.mail.yahoo.com/dr/launch?.tgx=fOt9ib247071

Thonhoff, “Medina, Battle of”. Handbook of Texas Online.

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qfm01

Truxillo, Charles. “The Inevitability of a Mexican Nation in the American Southwest & Northern Mexico.” My Space.

http://us.mg4.yahoo.com/dc/launch?.gx=1&rand=f09i257071

Walker, Henry P., “William McLane’s Narrative of the Magee-Gutiérrez Expedition”, 1812-1813”. Quarterly of The

Southwestern Historical Society,Vol.LXVI,no.2(Oct.1962); Vol.LXVI, no.3 (Jan.1963); Vol. LXVI,

no.4(April,1963).

Warren, Gaylord, “Long Expedition.” Handbook of Texas Online.

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/LL/gy11.html

Mexicans, Anglos & the First Republic of Texas, 1813

by Robin Navarro Montgomery, PhD

Preface:

Entering the second decade of the twenty-first century, the United States is being polarized alarmingly along racial and cultural lines. Of immediate concern is the widening breach between Hispanics and those of Anglo-American heritage. University of New Mexico professor, Charles Truxillo, for instance, is projecting that before the end of the 21st century a new country, to be called “The Republic of the North”, will be carved out of the southwestern states of the US and the northern states of Mexico.

This study addresses the crisis of social fragmentation in our country by laying an historical foundation upon which to resurrect a sense of common

national identity. Explored here are the shared roots of Anglo-American and Hispanic-American cultures in events surrounding the rise of the First Republic of Texas. Emphasized is the direct link between these events and the drive for Mexican independence from Spain which Father Miguel Hidalgo initiated on September 16th, 1810.

By portraying the decisive role of the blending of Anglo and Hispanic cultures in the rise of the first republic, the book is “Celebrating Togetherness.”

Acknowledgements:

Providing Inspiration for this study was the Visionaries in Preservation, VIP, Program of the City of Navasota,TX under the direction of City Manager, Brad Stafford, in cooperation with Mayor, Bert Miller, and former City Councilman, Russell Cushman, and the Montgomery County Genealogical and Historical Society, MCG&HS.

About the Author:

Robin Montgomery holds a PhD from the University of Oklahoma and has been a professor at Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Troy State Graduate Program in Europe and Oxford Graduate School. He is a member of the Oxford Society of scholars and has published extensively in international relations and in Texas History. His books on Texas History include, The History of Montgomery County(1974,86), Cut’n Shoot, TX: The Roy Harris Story(1984), Tortured Destiny: Lament of a Shaman Princess(novel-2001), Historic Montgomery County(2003), Indians & Pioneers of Original Montgomery County(2006 & 2010), March to Destiny: Cultural Legacy of Stephen F. Austin’s Original Colony(2009), co-authored with Joy Montgomery Images of America: Navasota (2012), and in publication: Roy Harris, Cut and Shoot, TX

Published by Texas Herald Press, 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Preface

Introduction

Chapter I:

Mexico(New Spain): From Cortéz to Hidalgo

Chapter 2:

The Era of Mexican and Texas Patriots Together

Selected Bibliography

Introduction:

In 1813, Texas was a part of Mexico which was, in turn, a colony of Spain. On April 6th of that year, the first independent Republic of Texas was established. Earlier, seeking to arouse his Mexican countrymen to the cause of independence, the soon to be president of the republic expressed the multicultural mix of his followers:

“Rise en masse, soldiers and citizens: unite in the holy cause of our country! I am now marching to your succor with a respectable force of American volunteers who left their homes and families to take up our cause, to fight for our liberty. They are the free descendents of the men who fought for the independence of the United States: and as brothers and inhabitants of the same continent they have drawn their swords with a hearty good will in the defense of the cause of humanity: and in order to drive the tyrannous Europeans beyond the Atlantic.” (bib.: “The First Republic of Texas”)

The man expressing these words was Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, whose mentor and inspiration was Miguel Hidalgo, a lowly parish priest in Dolores Mexico. In that town, on September 16, 1810, Hidalgo had given vent to words known to all lovers of freedom as the “Grito de Dolores”, a cry for freedom under the banner of the Patroness of the Americas, “Our Lady of Guadalupe”. “Long live Religion, long live America,” he cried. Hidalgo’s message spread across the length and breadth of his country, giving birth to a movement which by 1821 resulted, finally, in freedom for Mexico from its Spanish overlords. In the early stages of that struggle, Hidalgo commissioned Bernardo Gutiérrez as a Lt. Colonel in his Army.

Exploring the link between Hidalgo, Gutiérrez, and volunteers from the United States in establishing the first Texas Republic is the primary thrust of our story. We will begin with an initial survey of the historical class structure of Mexico, then proceed to the events giving rise to the “Grito de Dolores”. We will follow with a survey of the repercussions of Hidalgo’s Grito including the rise of Gutiérrez and the establishment of the first Republic of Texas.

The conclusion will explore the significance of these events for the blending of Hispanic and Anglo-American cultures.

Chapter I

Mexico (New Spain):From Cortéz to Hidalgo

Founding of New Spain & its Culture:

In 1519, an adventurer based in Spanish-controlled Cuba, Hernán Cortéz, undertook the leadership of an expedition to the coast of the mainland to the west. Upon landing, he established a town which he called Vera Cruz, the True Cross. Named for its colonial master, Spain, the surrounding land was known as New Spain. By 1522, Cortéz and his army had conquered the dominant civilization of the vast area of New Spain, the Aztec Empire.

Over the next three centuries, a highly stratified society emerged in the ever-expanding Spanish Colony. At the apex of society were those who enjoyed the accident of having been born on the peninsular of Spain. They were known as peninsulares, and they held the key political positions of the land, starting with the position of viceroy, vice king, the direct representative of the king of Spain. Next in the social hierarchy were those of essentially pure Spanish descent but born in New Spain. There were called criollos (creoles). Finally came the mixed bloods, those of some Spanish descent. First among these were the mestizos, of Spanish and Indian blood, then there were the mulattoes, a mixture of Spanish and African-American lineage. Holding the bottom rung of society were the Indians and African-Americans.

Over time the position of the Indian in New Spain became progressively more untenable. Not only were their numbers decimated by diseases brought by the Europeans, for which the Indians had no immunity, but the Indians also fell liable for tribute in time and labor to their Spanish masters.

Sustenance to cope with this condition of servitude came for the Indian in a dramatic fashion one day in January 1531. An Indian peasant, Juan Diego, now St. Juan Diego, was worshipping at the shrine of the Indian serpent goddess. To his grand surprise, amid bright light and bird song, the Virgin Mary appeared to him. She requested that Juan tell the Spanish authorities of her, asking them build a shrine to her on the sacred hill on which she stood. The faithful Indian did his best to meet the grand lady’s request, but alas, was unable to meet success.

Undaunted, the lady appeared to him a second time in the same place. This time she asked him to climb to the top of the hill and there pick red roses, placing them in his cloak. Although it was the dead of winter and besides, only cactus had ever grown on this hill top, the faithful Indian obeyed. And the roses were there. Placing them in his cloak as requested, he presented them to the priest. To the surprise of all, appearing on the cloak were not roses by an image of the lady made without human hands.

Placed in the nearby town of Guadalupe, the cloak became a shrine know as the “Virgin of Guadalupe.” Copies of the shrine appeared throughout the Americas. Worship of the Patroness of the Americas had begun.

Change Agents:

The beginning of the end of the highly stratified society of New Spain came in 1808. In that year, the French Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte, placed his brother, Joseph, on the throne of Spain. Napoleon took the legitimate heir apparent to the Spanish crown, Ferdinand VII, into captivity in France.

The reaction in New Spain to Napoleon’s coup was along class lines. The peninsulares supported the viceroyalty, hoping that way to continue to exercise power. On the other hand, the criollos and higher level mestizos, for the most part, looked to find some way to gain independence for New Spain in the name of the deposed king Ferdinand. The lower level mestizos and mulattoes, Indians and African-Americans, generally remained out of play of the politics, living as they had for centuries.

Rise of Miguel Hidalgo:

Miguel Hidalgo was born on May 8, 1753, near Guanajuato, New Spain. The early years of his education were

at Valladolid, now called Morelia, and he became a priest in 1779. Along the way, he learned several Indian dialects as well as French. The latter language he used as the bridge to take him to knowledge of the philosophy behind the French Revolution of 1789. Reading this literature was considered sacrilege in New Spain in those times.

By 1810, Hidalgo had become a priest in the village of Dolores, New Spain, not far from his native Guanajuato. He would on occasion travel to the nearby town of Queretaro where he would visit with other criollos and more cultured mestizos of like-minded philosophical bent. It was on these occasions that he became involved with a group bent on revolting against the French-supported peninsulare establishment.

With a loose coalition including most prominently a criollo military officer named Ignacio Allende, Hidalgo marked December 1810 as the time for the revolt to begin. Alas, however, word of the plan leaked to the peninsulare authorities prompting a momentous decision from Hidalgo, would he run or would he fight?

Hidalgo chose the latter option. It was thus on September 16, 1810, that Miguel Hidalgo rang the bell summoning his lower class flock and announced that the time had come for revolution in the name of religion and Independence, as subjects of King Ferdinand VII of Spain. Animated, his

flock followed him, bent on taking Mexico City. Along the way, they took on a banner emblazoned with the Image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. In the name of the holy catholic religion, they would rout the Spanish royalists, now under the influence of the French apostles of the secular ideas of the French Revolution and Enlightenment.

As Hidalgo and Allende led their undisciplined army toward Mexico City, violence and massacres were rife everywhere in their path. So much so that on the outskirts of the city, with victory in his grasp, Hidalgo hesitated, to the chagrin of the more military-minded Allende, and decided to forfeit a sure victory. Instead, he turned his army around and headed for Texas, seeking to gain support in the United States.

By early 1811, Hidalgo’s Army had lost several key battles but had managed to get to the state of Coahuila just below the line of the present border of Texas. During this time, Coahuila and nearby Nueva Leon as well Nueva Santander north of the Rio Grande were sympathetic to the insurgent cause. So was Texas.

Meanwhile, in San Antonio:

In 1773, San Antonio had become the capital of the Province of Texas. As Hidalgo was making his way north, the Spanish Governor in charge of the state was Manuel Salcedo. On January 21, 1811, Juan Bautista de Las Casas initiated a coup de etat against Salcedo. Salcedo received a sentence from the new administration to house arrest in a hacienda or plantation outside of Monclova, Coahuila. Managing the hacienda was an ally of Hidalgo named Ignacio Elizondo.

The sojourn of Salcedo at the hacienda of Elizondo was destined to be short-lived, for on March 2, 1811, the regime of Las Casas suffered defeat. His place was taken by Juan Manuel Zambrano, a loyalist of the royalist cause. The new regime reversed the sentence of Manuel Salcedo, and then sent troops to the Elizondo hacienda to release the former governor. Their task was easy, for Elizondo, the overseer of Salcedo, had by the time of their arrival, deserted the insurgent cause.

The fate of Miguel Hidalgo, Spring and Summer 1811:

These events coincided with the arrival of the main forces of Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende into northern New Spain. Hearing that Hidalgo was in the area, the traitor to Hidalgo’s cause, Elizondo, mustered a force together, and under the authority of a revitalized Manuel Salcedo, succeeded in luring Hidalgo and his army into a trap. The patriotic captives were escorted to Chihuahua where Salcedo presided over their trial, sentencing Hidalgo, Allende and the main leaders to death. Not only were they killed, but Hidalgo and Allende, along with two other members of Hidalgo’s high command, had their heads severed from their bodies and placed on pillars in public at Guanajuato. There they remained for some ten years.

Chapter II

The Era of Mexican and Texas Patriots Together:

Enter Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara:

Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara was a blacksmith of criollo lineage who spread revolutionary flyers within areas in the vicinity of the eastern reaches of the Rio Grande. As Hidalgo made his way north, Bernardo greeted him, receiving in return a commission as a Lt. Col. Hidalgo also made Bernardo his envoy to the United States. Although it was just after Hidalgo suffered death, Bernardo Gutiérrez did indeed make his way to the United States where he visited with Secretary of State James Monroe. A representative of Monroe, William Shaler, subsequently joined Gutiérrez in Louisiana and accompanied him to Texas, entering the state in August, 1812.

With Bernardo Gutiérrez as co-leader of forces was an officer of the United States Army, Augustus Magee, who soon resigned his United State’s commission. The resultant Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition was able easily to capture Nacogdoches, then it was on to the Trinity where they overcame the Spanish forces of Trinidad. From here they headed for San Antonio. En route, as they approached the Colorado River, word came that Manuel Salcedo, now back in power as governor of Texas, was awaiting them. Hence the expedition turned south toward Goliad and captured the Bahia Presidio there.

Governor Manuel Salcedo’s Army soon laid siege to the fortress of Bahia. However, with time, the revolutionaries ventured out victorious and set their sights on San Antonio. It was as they neared that city that Bernardo Gutiérrez spread the word to the citizens of San Antonio, quoted in the introduction, that he was on the way with support from Anglo-Americans.

The Green Flag Republic:

By early April, the expedition had achieved success. On April 6, 1813, Gutiérrez proclaimed the Republic of Texas and proceeded to write a constitution. Before reaching San Antonio, Gutiérrez’s military cohort, Augustus Magee, had died during the Bahia siege. However, the green flag that Magee had fashioned at the beginning of the Gutiérrez-Magee expedition in honor of his Irish ancestry symbolized the new republic, indeed known as the “Green Flag Republic.” Thus, the first Republic of Texas was headed by a Mexican, heir of Miguel Hidalgo’s revolution, and under a symbol of Irish-American lineage.

As President of Texas, one of the first acts of Gutiérrez was to bring to justice Manuel Salcedo and his cohorts, sentencing them to be imprisoned outside of the capital city. Thus did Bernardo Gutiérrez avenge the death of the executioner of Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende and their key followers.

Unfortunately, this great deed was mishandled as Antonio Delgado, the man in charge of the forces escorting Manuel Salcedo and company, had revenge on his mind. Salcedo had been responsible for the execution of Delgado’s father. Consequently, just outside of San Antonio, Delgado called for Salcedo and his colleagues to dismount and proceeded, with the help of his followers, to slit their throats. Not only this, but the executioners returned to San Antonio to brag about the matter.

This gruesome incident led to the alienation of many of the Anglo-Americans who were affiliated with the Gutiérrez government and they consequently left the city and state. Whether Gutiérrez had sanctioned the massacre of the Salcedo group is yet debated among historians. What seems for sure, however, is that this was one of the reasons that he was forced from office on August 4, 1813.

The Battle of Medina:

The man replacing Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara as President of the Republic of Texas was José Alvarez de Toledo. After an initial skirmish with a force under Ignacio Elizondo, on August 18, 1813, Toledo led some 1400 hundred troops into battle against the royalist General Joaquin Arredondo. This was near the Medina River. In the bloodiest battle in Texas history, all but about 100 of Toledo’s followers suffered death.

A primary cause of the debacle lay in Toledo’s decision to divide his forces by race. He created separate groups of insurgent Mexicans, Indians and Anglo-Americans. There was at least one African American among Toledo’s troops, a man named Thomas. The racial division of forces proved highly inefficient as representatives of these groups had been used to working together. Apart, they were ineffective. United upon their entry into San Antonio they had successfully proclaimed the first Republic of Texas. Later, however, divided, the republic fell, defeated. This defeat, however, failed to sever the link between Gutiérrez and Texas.

Gutierrez supports later filibustering expeditions into Texas:

In 1817, Francisco Mina, a Spaniard, sought to continue the Hidalgo rebellion by engaging royalist forces in southern Texas. Lending liaison aid and support to the unsuccessful Mina Expedition was Gutiérrez.

The First Lone Star Republic:

During 1819 to 1821, Dr. James Long embraced filibustering expeditions to Texas. The first expedition set up bases along both the Trinity and Brazos Rivers while the last operated at Bolivar Point off Galveston Bay. Representing the government of Dr. Long was a flag emblazoned with a white lone star against an immediate red background coupled to red and white stripes. Alternately, for a time, was a solid red flag with a white star.

Playing an endemic role with Long was the peripatetic Bernardo Gutiérrez. Gutiérrez was a member of Long’s council of advisors and slated to be vice president, should the revolution have succeeded in implementing the second Republic of Texas.

Interestingly, the person whom Long projected to fill the role of president was José Felix Trespalacios of the Mexican state of Chihuahua, a revolutionary also drawn from circles heir to Hidalgo. By the time of the Long Expedition, Trespalacios had been imprisoned several times by royalist forces; the last time he was placed among survivors of the ill-fated Mina Expedition. Managing to escape, Trespalacios made his way to New Orleans. There he made contact with James Long, becoming the nominal commander of the Long Expedition. He survived to become the first president of the post Spanish era Mexican State of Coahuila y Texas.

Gutiérrez de Lara recognized in an independent Mexico:

The final liberator of Mexico from Spanish rule was Augustin de Iturbide, who formally recognized the efforts of Gutiérrez de Lara for his significant accomplishments toward Mexican Independence. Reflective of the gratefulness of his country, Gutiérrez received election to the governorship of the Mexican State of Tamaulipas in

1824 as well as being named commandant general of that state in the following year.

In Conclusion:

It has been shown that by extension, Hidalgo’s revolution was intrinsically intertwined with events in Texas and the United States. Linked to Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara, the phase of the revolution in Texas reflected an intercultural mix, militarily, socially, politically and in terms of religion, a glorious chapter in the history of both Mexico and the United States.

Truly, on September 16th , and on April 6th, in unity we can proclaim, “Viva Hidalgo, Viva Mexico, Viva Texas and Viva los Estados Unidos”!

Selected Bibliography:

BOOKS:

Carter, Hodding. Doomed Road of Empire. New York: McGraw Hill, 1963.

Foote, Henry Stuart, Texas and The Texans. Vol. I; Austin: The Steck co., 1935.

Garrett, Julia K., Green Flag Over Texas: NY-Dallas: Cordova Press, 1939

Montgomery, Robin. The History of Montgomery County, TX. Austin: Jenkins co., 1974, & sesquicentennial ed.,

Conroe Sesquicentennial Committee, 1986.

Parkes, Henry Bamford. A HISTORY OF MEXICO. 3rd edition; Boston: Houghton Mifflin co., 1960.

Putnam, Robert. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York

Simon & Shuster, 2000.

Yoakum, H., History of Texas. Austin: Steck co., 1855.

ARTICLES:

Gutierrez de Lara, “ 1815, Aug.1 J.B. Gutierrez de Lara to the Mexican Congress. Account of Progress of

Revolution from the Beginning.” pp 4-29 in Lamar Papers, vol. I,(Austin-NY: Pemberton Press, 1968.)

“The First Republic of Texas”. New Spain-Index. Sons of Dewitt Colony.

http://us.mg4.mail.yahoo.com/dr/launch?.tgx=fOt9ib247071

Thonhoff, “Medina, Battle of”. Handbook of Texas Online.

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qfm01

Truxillo, Charles. “The Inevitability of a Mexican Nation in the American Southwest & Northern Mexico.” My Space.

http://us.mg4.yahoo.com/dc/launch?.gx=1&rand=f09i257071

Walker, Henry P., “William McLane’s Narrative of the Magee-Gutiérrez Expedition”, 1812-1813”. Quarterly of The

Southwestern Historical Society,Vol.LXVI,no.2(Oct.1962); Vol.LXVI, no.3 (Jan.1963); Vol. LXVI,

no.4(April,1963).

Warren, Gaylord, “Long Expedition.” Handbook of Texas Online.

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/LL/gy11.html

HTML Comment Box is loading comments...